Since I’ve lived in South Carolina, I’ve experienced the edges and remnants of hurricanes, what was left of the wind and the rain after the land broke up the storm. My parents met in weather school in the Air Force, and my brother and I grew up learning about cloud formations, high and low pressure systems, types of lightening. My parents’ understanding about weather was especially comforting when we moved to Omaha in 1990, a place with the most extreme weather of any we had lived so far. We learned about tornado warning systems, the safest place to shelter in a house. The four of us huddled together more than once in the basement, taking shelter. We knew about blizzard warnings, white out conditions, when it was too cold to be outside because the wind chill meant frostbite on your face and hands.

So in the days before Helene hit, I vaguely prepared, bought some shelf-stable food, filled up some water bottles. But I just assumed the land would break up the storm, that the mountains would dissipate the winds. We might lose power for a few hours or a day, if a branch hit a transformer or knocked down a line.

Instead I woke up Friday morning to a storm fully formed, super charged by the warm Gulf waters and the wet soil in its path. The winds topped 70 miles per hour, the rain came in sheets. We had already had inches of rain from an earlier storm that week, the ground was saturated, the roots couldn’t hold. We watched out the window as the neighbors’ trees across the street came down and looked next door at a 100 foot massive pine tree across two yards. We had only one big tree left on our property, a Leyland cypress on the back fence line, planted because they grow quickly and provide a landscaped screen. We had already lost a few in a previous ice storm. The wind pushed it out of the ground, it rests now on other trees, leaning dangerously across the back of our yard.

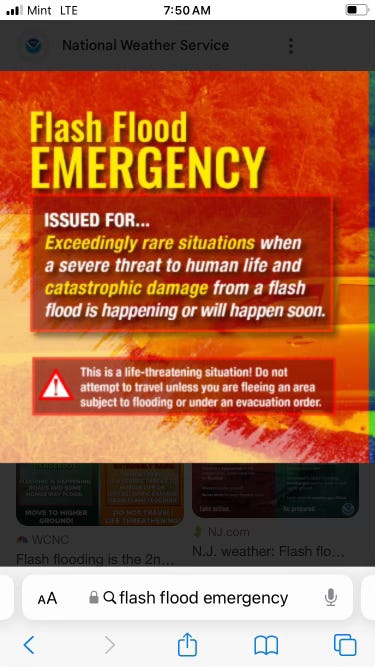

For a couple of hours we sat nervously in the living room with our kids, our phones pinging with alerts. The eye passed over us and it went quiet. I read on the phone an alert I had never seen, declaring a flash flood emergency, warning of a severe threat to human life and catastrophic damage. Our son read the alert over my shoulder, frightened, he asked us if we were going to flood. We live at the top of a steep hill near downtown Greenville, we bought the lot to avoid flood risk from waterways or rain. We assured him we were safe, that we wouldn’t flood. We avoided the corner of the house that could be hit by a tree: the only big tree left standing, a giant magnolia in the other neighbor’s yard. If it had come down in the early morning hours, it would have hit our daughter’s room.

I assured the children, the dog hid in his kennel, shaking. I knew our rivers and streams in Greenville were flooding, but my first thought was western North Carolina. How could the people in the narrow valleys and isolated communities there see these alerts? My heart sank. The power snapped, went out, didn’t come back on for five days. As I write this, ten percent of the Upstate still doesn’t have power, our internet is still out, schools are still canceled. Most of the roads in the city are clear, but the county bus lines run up to the mountains, and bridges are washed out, lines are still down, trees still block the way. Military helicopters and small craft providing aid fly over the house, the small downtown airport has become a part of the relief effort.

I threw away three bags of food, even though we tried to eat it before it went bad, grilling chicken wings to eat with pesto burrata pasta, a strange combination of necessity. We went down to collect my mom in Laurens, who stoically insisted she was fine (she did have a better emergency kit than us) but after two days of no power, alone, agreed to come and stay with us for a few days. When her power came back on, and we took her home, we found one of the ceilings in her bedroom had caved in from water damage. We didn’t realize the storm had blown off a roof air vent and soaked the attic and insulation with water. It will take months to fix.

We were so lucky, our cars and houses mostly unscathed, but it will still be thousands of dollars to take out the tree, to fix Mom’s ceiling. After a day of power, I felt confident enough to restock the refrigerator and it cost us $400. On a Buy Nothing Facebook group, I’m seeing pleas from families in the same situation, but they have no resources, they have no money to restock. Restaurants and food pantries and the school district are stepping up to provide free food, but some of these families have no transportation, no money for gas. Kids are going hungry, people are desperate for baby formula.

When we bought the house in 2017, Alex was a toddler and I was pregnant with Ellie. Two maples in the front yard were clearly sick and dying, the branches mostly gone but still close enough to the house and cars to cause significant damage. A beautiful maple in back was growing into the house, a tree service came out and warned the large branches were diseased and could fall and hurt us. We spent $5000 dollars to take them all out over a couple of years, money that was hard to scrape up with daycare costs. But we could do it, and it might have saved our lives. So many trees are down, in such a wide area, that there was no way everyone could have had this kind of protection. But clearly the suffering in this region is made much worse by the threadbare social safety net we have, and the poverty that families lived in before. If you can donate to help people rebuild, please consider sending money or donating food or clothing.

We are lucky that a cold front descending will push the latest hurricane away from our area, but it will mean people stranded in the mountains could face freezing temperatures soon, without power and water. The national guard is there, and search and rescue teams, and a thousand active duty military. Linemen are coming from Canada, and from states all over the country. A crew from Texas fixed the lines on our street. I know how lucky we are, but it has still been so stressful, especially because as a parent I was most concerned with taking care of the kids. Parents on the street invited ours to come over and play, we gathered at friends’ houses that had power, the kids played happily, my mom and my in-laws are helping. Alex asked for the first time yesterday when he could go back to school. We all miss normal.

Those trees are massive! I'm just hoping that people might believe that the climate has changed! Or the globe has warmed!

Stay strong and hopefully you'll be able to transition back to teaching as well as possible!

Terrifying. I am so glad that you are all OK. Please let me know if there are any local groups that we can support.